OCC History Center offers chance to 'revote' in centennial of Colorado City annexation

Establishing the look and feel of the annexation

election of 1917 - including old-fashioned clear-glass ballot boxes - are three

historically clad members of the Old Colorado City Historical Society (OCCHS).

From left are Don Hansen, Terry Lee and Marilyn Lee. Note that the

"ballots" are being cast with money - symbolizing the OCCHS plan to couple its

century-later annexation "revote" with donations.

Establishing the look and feel of the annexation

election of 1917 - including old-fashioned clear-glass ballot boxes - are three

historically clad members of the Old Colorado City Historical Society (OCCHS).

From left are Don Hansen, Terry Lee and Marilyn Lee. Note that the

"ballots" are being cast with money - symbolizing the OCCHS plan to couple its

century-later annexation "revote" with donations.

Westside Pioneer photo

|

This ended the saga of a town which had been founded during the region's first gold rush in the 1850s, had staved off Indian attacks, been a territorial capital and a county seat, then experienced its heyday as a gold-mill and railroad town (thanks to the Cripple Creek gold strikes of the 1890s) before slowly sinking into decline as the gold played out and the anti-liquor movement eliminated saloons as an income source.

In a lighthearted commemoration of that centennial, the Old Colorado City Historical Society (OCCHS) is inviting citizens to take part in an annexation “revote.”

“This year we celebrate 100 years since this big event,” reads a press release from Sharon Swint of the OCCHS. “If a vote was taken today, what would the results be? Between April and August 2017, the Old Colorado City History Center will be taking another vote. How would citizens vote with a century of hindsight? Should Colorado City have remained separate, or was annexation the right thing?”

The all-volunteer society owns and operates the History Center, which offers a bookstore and museum at 1 S. 24th St., along with special programs throughout the year.

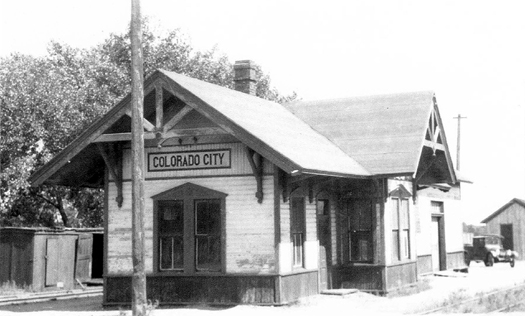

The Midland railroad station was built around

1904, serving passengers until it burned down in 1931. According to local

historian Mel McFarland, the location was on the north side of the train line, off

25th

Street (which had an at-grade crossing in those times), about where the Highway

24 westbound lanes are today.

The Midland railroad station was built around

1904, serving passengers until it burned down in 1931. According to local

historian Mel McFarland, the location was on the north side of the train line, off

25th

Street (which had an at-grade crossing in those times), about where the Highway

24 westbound lanes are today.

Courtesy of Mel McFarland

|

But don't expect an official tally afterward. Because the activity is doubling as a fundraiser, the OCCHS is unabashedly telling people they can multiply their votes through larger donations. One penny equals one vote while a dollar equals 100 votes. There is no limit to the amount of votes a person can “buy,” Swint explained.

The results in the 1917 election were as follows:

- Colorado Springs 4,483 pro, 1,354 con.

- Colorado City 638 pro, 461 con.

What people know today as “Old Colorado City” was actually the downtown area for a then-lightly developed 280-acre municipality. According to Westside civic

Dave Hughes portrays Colorado City

co-founder Anthony Bott during a Cemetery Crawl event by the Old Colorado

City Historical Society in 2014. Hughes is standing in front of Bott's prominent

gravesite at the northeast corner of Fairview Cemetery. Bott donated the land for

the cemetery.

Dave Hughes portrays Colorado City

co-founder Anthony Bott during a Cemetery Crawl event by the Old Colorado

City Historical Society in 2014. Hughes is standing in front of Bott's prominent

gravesite at the northeast corner of Fairview Cemetery. Bott donated the land for

the cemetery.

Westside Pioneer file photo

|

At the time of the annexation vote, Colorado City had 4,000 residents, a $1,700,000 land valuation, two parks and a fire station.

The election followed many years of discussion and negotiations between the leaders of the two towns.

An article by Suzanne Schorsch in the April issue of the OCCHS' West Word newsletter suggests that Colorado City's political direction at the time may have contributed to the situation. It had little or no debt, and while this was a cause of pride for some, the status had resulted from its leaders putting “the lack of debt above growth and improvements,” Schorsch writes. “Colorado City was not dead, but it was surely stagnant.”

The town's main newspaper in that era, the Colorado City Independent (no connection to the current weekly), editorialized in favor of annexation. Its reasons included the expectation of noticeably lower taxes and insurance rates, improved health services, a financially sensible water utility, a continuation of the postal substation and a chance to “become residents of one of the foremost cities of the state, a city known in all parts of America.”

Regarding water, Swint noted that “many new pipelines were put in after the annexation.”

Schorsch's article points out the anti-annexation argument that Colorado City “already had the same amenities as Colorado Springs: lights, gas, water and street cars [and] it was better to rent water from the Colorado Springs Water Works

In a project led by Dave Hughes, volunteers

with the Old Colorado City Historical Society designed, then fundraised to build

this eight-sided monument in Bancroft Park in time for the 150th anniversary of

Colorado

City's founding in August 2009. The location is next to the Garvin Cabin.

In a project led by Dave Hughes, volunteers

with the Old Colorado City Historical Society designed, then fundraised to build

this eight-sided monument in Bancroft Park in time for the 150th anniversary of

Colorado

City's founding in August 2009. The location is next to the Garvin Cabin.

Westside Pioneer file photo

|

Foes also alleged that Colorado Springs city employees were paid more than their Colorado City counterparts and would want even more, her article relates. In summary, “Colorado City had gone through a cleaning up of the city through [liquor] Prohibition and was well on its way to seeing a better day without Colorado Springs.”

Not just Colorado City was worried about the deal. “The source of the biggest friction,” historian Mel McFarland says in his recent Cobweb Corners column in the Westside Pioneer, was Colorado Springs officials believing “that it was they who were getting the worst part of the bargain!”

World War 1 may have affected the anti-annexation turnout, according to Hughes' book, “Historic Old Colorado City” (published in 1978). “Some say that had not all the boys been 'over there' in the first WW, the vote would never have carried,” his book opines.

But when the vote did carry, Hughes continues, “the independent, proud pioneer spirit lived on even after Old Town became simply 'Westside'… Westsiders retained their identity and worked on the Midland Railroad and Golden Cycle Mill right up into the 1940s.”

Another anti-annexation fear, stated in Schorsch's article, turned out to be prophetic. This was “that the Colorado City business center, which did have vacancies due to the outlawing of saloons, would become even less important, causing an increase in empty buildings.”

This phenomenon took place despite the saloons returning (courtesy of Prohibition being repealed in 1933). By the 1970s - with the railroad and mill long gone and the 1960s-built Highway 24 allowing motorists to bypass Old Town - more than 40 percent of the storefronts stood empty, Hughes and others have recalled.

In response, a public-private revitalization effort blossomed in the mid-'70s, which led to several building renovations, as well as the landscaping, lighting, sidewalks and free parking lots that have lasted into present times.

Side note: An offshoot of the revitalization was the the name, “Old Colorado City.” According to Hughes, who coordinated the historically themed effort in concert with local merchants, he coined the name as a result of conversations with Gene Brent, then-owner of an Old Town gun shop, and prominent Westsiders Luther McKnight and LeRoy Ellinwood. (See Pioneer article at this link).

Westside Pioneer article

(Posted 4/10/17, updated 4/11/17;

Community:

Old Colorado City History Center)

Would you like to respond to this article? The Westside Pioneer welcomes letters at editor@westsidepioneer.com. (Click here for letter-writing criteria.)